Before Marco Antonio Santana could speak English, he was speaking computers. The 32-year-old grew up in a Dominican family in New York City and now helps install and repair high-speed fiber optic internet for more than 180 units in low-income housing on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

“I’ve been a nerd my whole life,” he tells me as he connects a delicate bundle of fiber optic cables into a splicer at his NYC Mesh studio.

We climbed to the roof of this 26-story building for stunning views of the city’s water towers, bridges and pre-war architecture. There, multiple remote antennas and routers wirelessly connect to other rooftop nodes as far away as miles away in Brooklyn, along the East River. Here’s a glimpse into the growing network NYC Mesh has built over the past few years.

NYC Mesh is not an internet service provider, but a grassroots, volunteer-run community network. The goal is to create an affordable, open, and reliable network for all New Yorkers to use the Internet for daily and emergency use. Santana said the group’s members want to help people determine their digital future and “return the internet to what it once was.”

Internet access is an important part of our daily lives: employment, health, education, communications, finance and entertainment. However, there is a huge gulf between those who are able to connect and those who are not. According to data technology company Broadband Now, an estimated 42 million Americans lack access to high-speed internet.

The lack of low-cost, reliable broadband options puts a heavy strain on poor, Black, Latino, Indigenous and rural communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when networks are the only lifeline, the crisis becomes even more acute.

“There are serious issues with access,” said Prem Trivedi, director of policy at the Open Technology Institute. “It’s not sustainable for students to do their homework in fast-food parking lots to get free Wi-Fi.” “It’s an intermittent connection that requires upending your life to meet your most basic needs.”

Digital equity is a tall order. That means going up against a handful of existing ISPs (Xfinity, Spectrum, AT&T, Verizon, etc.) who dictate prices, terms of service, speeds and where infrastructure is built.

“ISPs are always trying to maximize profits. We just want to connect our members at the lowest cost possible,” said Brian Hall, a lead volunteer and one of the founders of NYC Mesh.

Sean Gonsalves, associate director for communications at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, said historically when private markets fail to provide basic goods, communities step in to fill the gap. “That’s how America’s rural electric and telephone cooperatives were born a century ago.”

NYC Mesh also has public Wi-Fi hotspots across the network. Security technologist Bruce Schneier once called sharing a wireless connection with your neighbors “basic courtesy,” akin to offering a hot cup of tea to a guest.

Unlike mainstream ISPs that monitor online activity and sell the data to advertisers, NYC Mesh does not collect personal data, block content, or track users. Hall estimates that thousands of people connect to the network every day through more than 1,300 different installations.

NYC Mesh is the largest community network in the Americas, second only to Guifi, the world’s most extensive grassroots mesh network based in Spain. Guifi started providing broadband internet to rural Catalonia two decades ago and has grown to serve more than 100,000 users. Like NYC Mesh, it is a bottom-up, volunteer-led initiative based on common internet infrastructure and cost sharing.

By publishing extensive documentation on installers, equipment, and technology implementation, NYC Mesh provides a blueprint for other community broadband projects. Its website is a treasure trove of open source material that can be copied and adapted by groups.

Take Philadelphia Community Wireless, for example, which began building much-needed Wi-Fi hotspots in areas around Philadelphia during the pandemic. Philly Community Wireless now partners with local independent ISP PhillyWisper to connect up to 100 active devices per day, while also working with local organizations to distribute computers to residents and install solar and PurpleAir monitors in community gardens.

This model shows communities how to take control and build alternative digital ecosystems. “You are not just a passive consumer of the utility but an active participant in its construction and maintenance,” said Alex Wermer-Colan, the group’s executive director.

Developing a networked metropolis

On a hot afternoon in early August, two NYC Mesh volunteers were adjusting a newly installed router on the roof of a four-story brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn. There is a direct line of sight to another node half a kilometer away, so the path for transmitting signals between the two wireless antennas is clear. Lead installer Quincy Blake, wearing a backpack and a slender ponytail, tests the signal strength on his phone and then moves the router a few centimeters more until he finds the sweet spot.

Within an hour, a cable dropped from the roof and connected to the home router in Willard Nilges’ apartment. Nilges, who works as a programmer by day, now uses Spectrum to deliver roughly twice the upload speeds at a fraction of the cost.

Nilges has since become a loyal volunteer for the group, installing and writing code. “NYC Mesh is a community. It’s neighbors taking care of each other,” they told me via the group’s online Slack workspace.

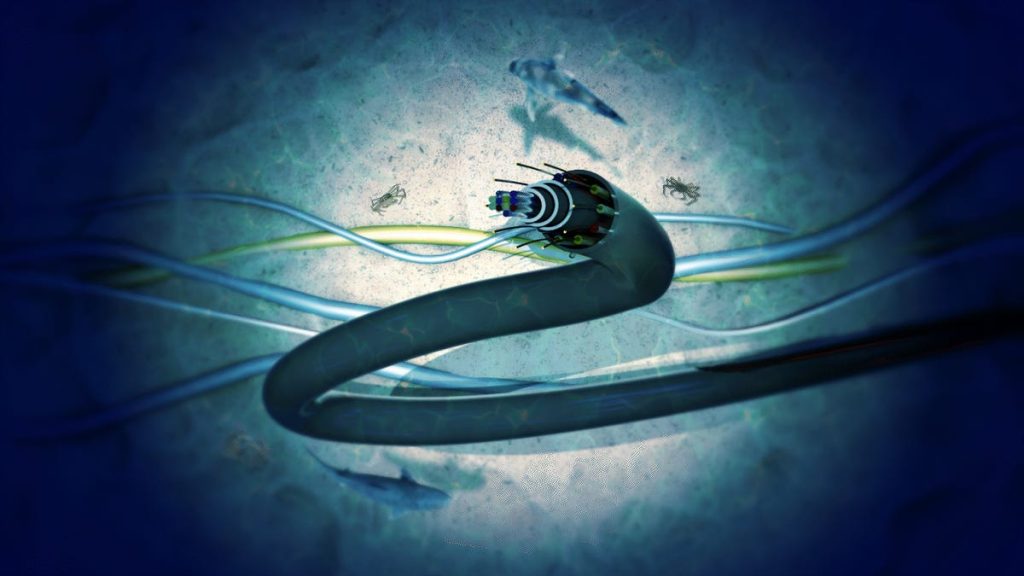

A mesh network is a system of multiple nodes and hubs (also called access points) that communicate with each other via signals from remote wireless routers and rooftop-mounted antennas. NYC Mesh also has “super nodes” with full-sector antennas and fast-connect gateways that connect to the internet, often via terrestrial fiber optics. The more devices that transmit data, the further the network spreads.

The grid concept is the basis of the Internet, which began in the late 1960s with a network of just four host computers and has grown to include billions of devices around the world. Like local mesh networks, the Internet is a complex mesh structure in which information travels from one point to another until it reaches its destination.

Because mesh networks are decentralized, there is no single point of failure and users can find a reliable connection in an emergency. If a node is blocked or loses signal, the network automatically looks for the most direct path available to send data. “The network is self-healing,” said Dan Miller, a New York City Grid volunteer. Miller, who works as a computer engineer for an aerospace company, built a mesh hub on his roof and unlocked entire dead zones to connect residents and businesses in Bushwick, Brooklyn.

To a layman like me, a wireless mesh network is similar to the New York City subway, a circuit made up of stations and routes. Building nodes are connecting stations at street level, and community hubs act as transfer stations where you can reroute to several different subway lines. Some routes are faster than others, but sometimes bad weather and aging infrastructure can hinder the route.

Wireless mesh networks rely on line-of-sight connections, which can be challenging in cities with jagged skylines, especially when you can’t access the tallest buildings. Although the signal provided by NYC Mesh is sufficient for most residential uses, rooftop wireless routers are susceptible to interference from rain and wind.

The organization is actively trying to build more fiber-optic line connections that can provide faster download speeds and greater bandwidth than Wi-Fi. Although fiber optic infrastructure is much more expensive to install up front, its broadband connections are more reliable in the long run, providing superior performance to traditional infrastructure.

ISPs such as Verizon and AT&T charge customers for data traffic and lease their equipment and cables at inflated prices. NYC Mesh legally bypasses commercial ISPs and accesses the Internet directly through a process called peering, where networks connect for free through Internet exchange points and share traffic with each other.

As for cost, for new NYC Mesh users to purchase the equipment, the organization requires a one-time $50 setup fee and monthly on-demand donations to keep the network running. Core technical staff often opt for DIY (“do-it-yourself”) installations, with users requesting troubleshooting or assistance through the Slack app. “If you have a problem, you can message someone and they’ll fix it the same day if they can,” Black told me.

Anyone is free to join, as long as they keep the network open and extend it to others. Registration is completed through a simple online form, then submit a panoramic roof view to see if there are clear sightlines to neighbor nodes or hubs.

The spirit of “sharing with your neighbors” makes community building a core element of any mesh network. NYC Mesh has no hierarchy, but a core team of about two dozen active installers and administrators. Everyone who buys a router and connects to the network is a member, not a customer. When asked about the structure of the group, the typical response was “alphabetical.”

Volunteers can come and go as they please. Monthly gatherings usually have a handful of “newbies” and there is talk of a need for volunteers and advocacy to expand into more communities and boroughs. “It’s all about planting 1,000 seeds and seeing what happens,” chief installer Rob Johnson said in a June speech about strengthening Harlem’s grid infrastructure.

There are many ways to get involved, from crimping wires to outreach, and no technical experience is required. Volunteers are out in the field learning how networks operate, how cables work, and how equipment is configured. This hands-on participation is one way NYC Mesh demystifies the Internet.

Internet giants and local pioneers

New York City has a population of over 8.5 million, more than twice the population of Los Angeles. Before the pandemic, New York City had an estimated 1.5 million residents, most of whom lived in poverty and had neither housing nor mobile internet connections. NYC Mesh needs more funding and outreach, as well as lots of volunteers, to serve all low-income and marginalized communities.

Two and a half years later, the new administration drafted a revised proposal to provide free wired Internet to thousands of Section 8 housing residents. The city’s Big Apple Connect program, in partnership with Charter (Spectrum) and Altice (Optimum), provides billions of dollars in subsidies to cable TV giants to provide services based on outdated legacy infrastructure.

“The large existing private providers are extracting wealth from communities without giving them a say in the outcomes,” said Sean Gonsalves, director of ILSR’s community broadband network program.

In the United States, the internet market is dominated by oligopolies notorious for service restrictions, high prices and a lack of transparency. In 2018, Spectrum (formerly Time Warner Cable) was forced to pay a settlement of more than $174 million for defrauding millions of customers in New York. The state attorney general’s lawsuit alleges that for at least five years, Time Warner Cable knowingly provided slower than advertised speeds and inferior service.

“A big reason for customer dissatisfaction is that they think broadband providers are taking advantage of us,” said Trey Paul, CNEWS.COM.IN’s senior editor for broadband.

ISPs often attract customers with competitive prices and then mark them up a year later – in some cases by more than 200%. Paul said it was also standard practice for major providers to charge hidden fees for equipment rental and maintenance, leaving customers with higher monthly bills than advertised.

Price discrimination is also common. A 2022 study by Digital Equity LA found that Charter Spectrum offered the best speeds and cheapest prices to the wealthiest neighborhoods, while customers in poorer areas experienced slower service, higher rates and Worse terms and conditions. Another recent study by The Markup found similar examples of digital redlining. In several cities, AT&T, Verizon, Earthlink and CenturyLink provide poor broadband service to low-income, black and Latino communities.

Chris Vines, a grassroots advocacy organizer at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said insufficient digital access exacerbates social and economic isolation in inner cities and rural America. “Private ISPs don’t have the profit margin to provide Internet in these areas,” Vines said.

Mapping the problem

It’s difficult to accurately gauge the extent of the problem, according to the Federal Communications Commission’s broadband coverage maps, which have a long history of inaccuracies. The map is notorious for using flawed metrics to inflate coverage and miss large swaths of the country. What’s more, the FCC relies on major ISPs to self-report their data, allowing them to submit advertised bandwidth, not the actual speeds customers receive, nor the (often costly) rates they have to pay.

Although the FCC released a more detailed map last year, critics say it’s still deeply problematic. “There are still thousands of places that should have access to high-speed, reliable internet but they’re not even on the map,” said Gonsalves of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance.

Relying on inaccurate broadband data is also dangerous: The map is used to determine how federal grants for high-speed internet infrastructure are used.

For many internet advocacy groups, fixing the broken broadband market means pushing for open access solutions modeled after Ammon Fiber in Idaho or Utopia Fiber in Utah. With an open access network, a city or region can build and operate the physical infrastructure as a form of municipal broadband. Multiple providers then compete for users on the network, which can lower customer costs and expand coverage. In Ammon, for example, residents can choose from a wide range of national and regional ISPs at affordable prices, some of which offer high-speed plans for as low as $10 per month.

A major obstacle to open access is the unfettered control of telecom giants, which don’t like competing for market share and have no incentive to support non-profit alternatives. Gonsalves noted that as the only game in town, existing providers view community broadband networks as an “existential threat”.

Private ISPs also have powerful lobbying power, which they use to block new business models and limit competition. At least 16 states have “preemption laws” that either outright ban municipal broadband networks or create legal barriers to investment in community-led or government-owned networks.

Many of the smaller, volunteer-based networks currently operating do not appear to have received much backlash from the major ISPs, perhaps because they are still viewed as minor players in the market. “It’s David versus Goliath,” said Alex Wermer-Colan of Philadelphia Community Wireless.

Charter, Optimum and Verizon all declined to comment specifically on community-managed broadband organizations like NYC Mesh. On the digital divide front, the three providers noted their participation in the FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program, which provides eligible low-income customers with broadband subscription subsidies of up to $30 per month and one-time device discounts. However, families at or below the poverty line face multiple logistical challenges in accessing subsidies, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. Additionally, program funding is expected to be exhausted by summer 2024, which will deprive current enrollees of subsidy opportunities. Gonsalves said that while the ACP is a step forward, it is just a Band-Aid solution and does not solve the problem of high access costs in the first place.

Community Smart Garden

When NYC Mesh began growing its network nine years ago, it wasn’t alone. A group called the Red Hook Initiative built its own wireless network in late 2011 to provide free online access to residents of a remote, mostly black and Latino beachfront community in west Brooklyn.

When Hurricane Sandy hit the region in 2012, the fledgling Wi-Fi network became a life raft to the outside world. RHI senior communications manager Maddy Jenkins said no information was available to the Red Hook community. He was a teenager when the storm hit. “We have no gas, no running water and no electricity.”

New centers were built almost overnight, with mesh networks enabling residents to communicate with relatives and receive disaster relief. Over the years, the network peaked at 17 access points around local parks and businesses. But when the pandemic hit in 2020, its ambitious plans to expand coverage to the entire community stalled. “There were a lot of factors at play, and the Wi-Fi project didn’t work out the way we hoped it would,” Jenkins said.

Nonprofits and community groups who want to improve local internet access face bureaucratic, technical and financial challenges. Community networks must be self-sustaining, with a large enough support structure and sufficient funding to address ongoing maintenance issues and other setbacks.

The Meta Mesh Wireless Communities group is achieving this by transforming its mesh network project into a full-fledged not-for-profit ISP called Community Internet Solutions in 2022. With a grant and new partnerships, it was able to grow the organization and invest in infrastructure, which now has about 120 users around Pittsburgh. Community Internet Solutions hopes to connect 1,000 community members over the next six months, providing low-cost Internet access to the most hard-to-serve communities. “Our work is meaningless without the voice of the community,” said Executive Director Colby Hollabaugh.

connecting roadblock

Many community-led broadband projects have struggled to get off the ground. In 2020, Steve Williams began to build a community Mesh provider for Los Angeles, following the example of NYC Mesh, focusing on providing Internet services to the large homeless population in Venice Beach. Three years later, LAX Mesh is still just a web page and an email list.

“The first step is to bring the volunteer community together,” Williams told me via email. He was unable to do so mainly due to family and work pressures. But he envisions the next step: establishing a proof-of-concept in several communities. Have residents sign up to gain experience running the network and making it reliable. Engage with the community. Find a nonprofit foundation or other sponsor.

Maintaining momentum through a steady influx of volunteers is another challenge, even for an active group like Philadelphia Community Wireless that has successfully built local connections and business partnerships. “We have such a huge need for installations that it’s kind of beyond the capacity of our volunteers,” Wommer-Colan explained. Another hurdle is getting into buildings to accommodate more mesh antennas.

Although some grassroots broadband projects have failed to scale, a solid foundation has been laid. In the Boston area, Mass Mesh was driven by a desire to provide net-neutral, community-controlled access shortly after the FCC abandoned net neutrality in 2017. (Without net neutrality, ISPs have the clear right to block, discriminate, slow down, and access networks). But Mass Mesh has been unable to scale beyond six active nodes due to supply chain shortages of key router equipment. Founder James O’Keefe said the group hopes to relaunch in 2024.

Another organization is the Portland, Ore., Personal Telecommunications Project, which began more than two decades ago and operates multiple free open-access networks throughout the city. In its heyday, the small nonprofit established a network of about 140 hotspots and now has about 40 active nodes. The Personal Telecommunications Project has been pushing local governments to invest in a countywide fiber network over the past few years, acting more like an “Internet freedom group,” said Russell Senior, president of the Personal Telecommunications Project.

Senior said giving power to broadband operators will never solve the digital divide: “The only way to subsidize people who can’t afford broadband is to control costs. And the only way to control costs is to let broadband operators own the public resources.” Infrastructure . ”

No one really owns the Internet. This massive, global, decentralized system of interconnected networks is not owned by any single government, utility company, technology monopoly or telecommunications provider.

In addition to the entities that control the infrastructure, servers, data centers, web browsers, and hardware determine whether and how we exchange information. We live in a society where only a few companies have the capital and power to shape our digital future.

At NYC Mesh’s monthly gathering in July, core member Daniel Heredia asked attendees to brainstorm ideas for outreach in areas of need to close the broadband gap. In the final slide, the battery on Heredia’s computer died and the screen went black. “The more technology, the more problems, right?” he joked.

Internet access—the most important technological development of the modern era—should not be a luxury. Community-led broadband organizations like NYC Mesh cannot overcome this divide alone, but they can ensure that more people are empowered to participate in their daily lives. They give us a glimpse of what things would be like if everyone had free broadband.

Correction, September 25: This story initially incorrectly described which company was being sued by the state of New York over internet speeds and service provided compared to what was advertised. The company sued by New York State was Time Warner Cable, which was later merged into Spectrum.